Introduction to Cognitive Maps

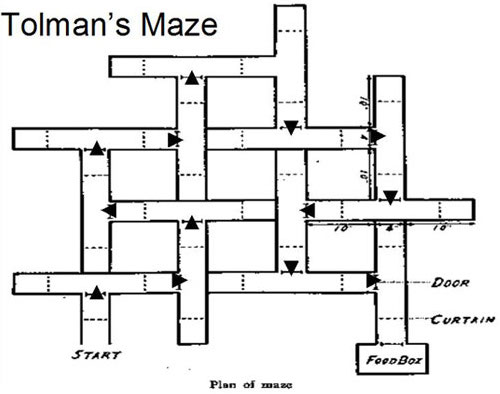

Classic work in rodents revealed the existence of so-called “cognitive maps”: internal models of the external world that allow for strategic planning and inference making. For example, Edward Tolman demonstrated in 1948 that mice will spontaneously use previously unseen shortcuts during maze exploration, suggesting that they had learned an abstract understanding of their space, rather than learning a sequence of reinforced “left, right, left, left” decisions as the conventional wisdom of behaviorism would have suggested.

It turns out that humans are just as capable in using cognitive maps for spatial navigation. In fact, modern research has conclusively demonstrated that cognitive maps are a fundamental organizational principle for all kinds of knowledge, helping scaffold and facilitate learning and memory in a variety of circumstances. For example, cognitive maps lie at the heart of statistical language learning in infants and in the learning of social hierarchies, and have even been shown to help inference in more abstract spaces, such as a two-dimensional space defined by bird neck and leg lengths (called “bird-space”). Critically, however, it remains unknown whether cognitive maps also support the organization and implementation of higher-order cognitive processes such as cognitive control or attention, the focus of this line of work.

In this line of work, I investigate how people learn relational hierarchies and use cognitive maps thereof to guide cognitive control. Specifically, participants observe a sequence of images derived from a random walk through a network structure (unseen by participants), as shown below.

By observing this random walk, participants integrate the relational structure of the (unknown) hierarchy and create a cognitive map of their relationship. To measure cognitive map formation, we employ a variety of behavioral phenomena, including the “cross-cluster surprisal effect” (Karuza et al., 2017) and the odd-one-out test (Tompson et al., 2019).

After forming the cognitive map, participants complete a Stroop task during a second random walk (as shown above). Each half of the network structure is associated with different level of cognitive difficulty. For example, the left half is associated with only congruent Stroop stimuli (e.g., RED or BLUE), while the right half is associated with incongruent simuli (e.g., GREEN or ORANGE). Critically, one member of each community is ommitted from the random walk during this phase. Finally, in the transfer phase, we pair these ommitted members with various Stroop stimuli. If participants can use their cognitive maps to guide cognitive control, then they should anticipate difficult (incongruent) Stroop stimuli for the members from the incongruent community, even if those members that were never directly paired with Stroop stimuli previously.

Data collection and research for this project is ongoing. In other variants of the task, we employ a variety of other stimuli, including faces, negatively and positively valenced images, and abstract fractal images. This work will have important implications for the nature of human intelligence and how cognitive maps can guide attention and cognitive control.